Avoiding Disaster - From Paper to Digital Prototype

- Pettersen L.

- Sep 3, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 6, 2025

As I start my final semester as a game development undergraduate student, I thought I should share some of the processes behind our upcoming game, a multiplayer shelter-building competition called Avoiding Disaster. This time around, I’m managing a team of other 8 amazingly talented students, so I’ve been doing my best to be sure that we make good use of the limited time that we have to create the project while also steering clear of rework and confusion as much as possible.

For a game designer, usually just having good documentation is considered the go-to solution for this challenge, but while we do have one of those as well, it’s often the case that the design document is created as a way to give a complete overview of a project before you have any idea if your game is going to be any fun. Sure, the documentation evolves, but if you are on the clock and this evolution is only driven by a process of constant rework, then you may end up having to commit a lot more often to your initial decisions just because the time is running out.

That is why I decided to take a cue from my good friend and veteran game designer Scott Rogers, who is a huge inspiration for me and once told me about an exercise he used to do with his students at the New York Film Academy, which was creating a board game version of their games before doing the digital version.

This proved to be a great help in finding a loop that we were satisfied with and preventing design flaws that would end up making us throw away a lot of code.

Here are a few of the things that we learned if you ever decide to try this approach:

“I believe that 75% of problems with a game design can be solved with a paper prototype.” - Scott Rogers

1 - Know what you want to test!

The idea of paper prototyping isn't really anything new in software development. It is actually often employed by UX designers to quickly test their projects by quite literally drawing an interface on paper to check for usability issues before any coding is done. The thing about good tests, though, is that they are designed with a clear purpose in mind.

In our case, things seemed somewhat clear at first, as the game loop was decided quite early: Cooperate to build shelters to survive incoming disasters and compete for limited spots inside said shelters since there's no room for everyone. That said, just by reading this loop idea, I’m pretty sure it’s already clear how this game could be designed in several ways. The concept of collaborating and competing at the same time seemed very exciting to us, but figuring out how to do it was not as easy as it seemed.

How can we make players build together instead of alone? Is there an elaborate crafting system? How and when do disasters occur? These are just a few examples, but any definitive answer to these questions can result in very different game rules, and some of them may be more restrictive and not quite as fun as the alternative.

One mistake that I made when I told the team that I wanted to create a board game to playtest our loop was not realizing that for some of the other members of the design team, a board game seemed to be a completely different experience from what we were trying to build. Because of this, some of the prototypes that they proposed ended up looking a lot more like something inspired by the theme of our game than an actual test version, since there was no attempt to simulate the systems that we were going for. While we did get some nice ideas from those, this was a communication error on my part.

When creating your prototype, be sure to think about what you are looking to figure out and use the tools at your disposal to actually simulate that experience. For that, our next topic may come in handy!

2 - The tools of the trade

Miniatures, dice, cards, maps… These are the obvious tools that we think of when we start making a paper prototype. But before just using them the exact same way you see in popular games, like deciding movement or the success of actions with the roll of the dice, we can get a lot more out of these tools if we try to think with more care about what we want to emulate, especially if it’s something that will actually need to be coded. This way, you can end up helping your programmer by figuring out specific rules and formulas, which is something that would be expected from a technical game designer.

Cards, for instance, are my favorite tool in the kit. A shuffled deck can often simulate random systems or events better than a dice roll, since you have control over probability by changing the population size of resources. Placed face-down on a board, they can emulate a mysterious item one has yet to reveal. In a player’s hand, they can become inventories, possible actions, or even debuffs like infection counters (looking at you, Nemesis). Here is a simple example from my prototype:

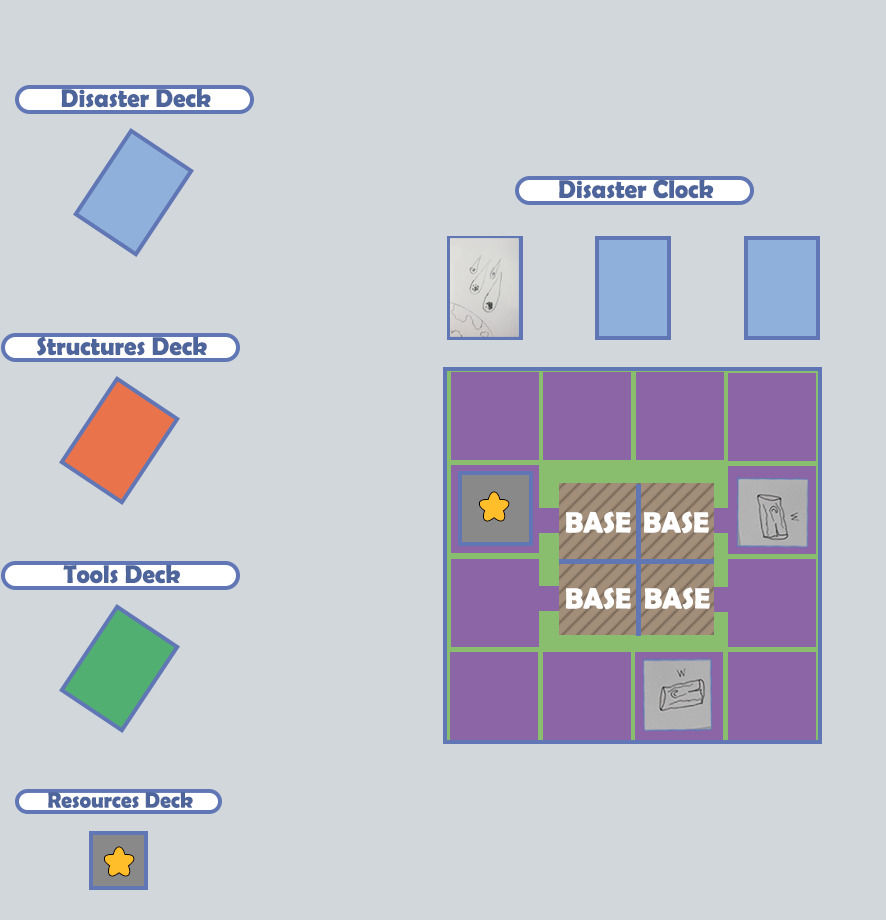

In Avoiding Disaster, a match ends after all the events on the Disaster Clock are activated and their effects are resolved. This is when we check which player has the most building points to decide who won. This is actually something that didn’t change much from the paper prototype. As you can see from the anatomy of the board in the picture:

Disasters are taken from a pool called the Disaster Deck and placed face-down on the board, representing the rounds of the game. After the players moved to farm resources or built structures on their bases, they would roll a die to see if a disaster was triggered before the end of their turns and would add the result of the roll to a separate counter, called the Disaster Counter. If this sum reached a certain amount, a disaster would strike the board.

For every time that this event wasn’t triggered, we would increase the Disaster Counter by one unit. This meant that the game would not activate disasters early on since the counter was low, but would increase the chances of unleashing one after each passing turn, allowing us some control over the amount of time that a round would take while keeping the element of surprise of a disaster striking out of the blue. This formula is pretty similar to the actual logic implemented in the digital version.

3 - Playtest, playtest, playtest

By far, the most useful thing you can get from an early prototype of any kind is player feedback, and this is especially true for a multiplayer game like ours. Having our team and friends play a version of the game early allowed us to quickly get everyone on the same page about what we were going to build and get invaluable input on what was working or not.

This proved to be a much more inclusive process because we were building over something that we were actually testing, and since creating the paper prototype was much more effortless than creating a digital proof of concept version, testing was quick and everyone was more receptive to criticism and changes, alleviating much of the stress of suddenly realizing that the players just found another way to completely break your game.

During our tests, a lot of changes were made to fit the dynamic playstyle that we intended. In both digital and paper versions, resources like wood and ore give different bonuses to the defense of a shelter when used as crafting materials to build structures, with wood giving fewer defense points. But in the board game, the only thing that made wood an interesting material was availability, since ore was difficult to come by. This made players prioritize grabbing it whenever it appeared on the board, turning the game into a race for the rarest resources instead of a race for points and survival.

We wanted the crafting in the final game to be more free-form, making wood something that you would actually want to pick from time to time. This made it clear that rarity was not the best solution to the problem. Instead, we added a weight system and allowed characters to hit other players to drop their resources. While carrying ore, characters would move a lot slower, so it became a risk/reward situation where carrying a heavy item required more skill and stealth. Since you get points every time you build something and lose points every time you die or a structure you built is destroyed, this change meant that players started to choose wood resources more often to quickly build an advantage.

In conclusion, there are a lot of strategies that you can employ when trying to figure out and communicate your game ideas. I’ve used Machinations to investigate the balance of economies, came up with ideas on the fly during game jams, made one-page documents at work, design review documents at college, game design documents, and illustrations of mechanics... Heck, Hideo Kojima designed levels for Metal Gear Solid out of Lego pieces. That said, I’ve yet to come by a solution that helped me as much in the early development as a paper prototype, so I definitely urge you to try making one, and if you do, I hope that this post was able to give you a few ideas. For now, I leave you with a video of an early proof-of-concept version of our game, which is no doubt a fruit of this experiment.

Comments